Confronting uncomfortable truths

Our Work Reflections Resources

By Katherine Lim / 23.02.2023

What we’ve been learning from attempting to decolonise our research practice.

By Katherine Lim / 23.02.2023

Colonisation has left a horrible legacy, and the dispossession, genocide and repression of Indigenous people and their cultures continues today. As an intersectional feminist organisation with predominantly settler/coloniser roots, it’s crucial for us to attempt, however imperfectly, to play our part in dismantling it.

We’ve recently begun the difficult process of attempting to decolonise our own research practice. It’s the start of a long journey, involving hard conversations, self-reflection and listening. We’re releasing a new paper, to share our recent lessons with others from similar backgrounds who are hoping to do the same. Here’s what we’re learning.

One: We're implicated

Whether we intend to or not, everyone who benefits from colonialist systems, structures, and worldviews is implicated in perpetuating them. Including, of course, us here at EQI. We, as an organisation, are largely based in an urban, high-income context, with a majority settler/coloniser staff. Many of us are also university educated with tertiary degrees, which affords a certain level of privilege. And so, we benefit from a power imbalance weighted in our favour, from the language we grew up speaking, to where we’re able to travel, to what we can write about and why.

If we don’t attempt, however imperfectly, to counter the impacts of colonisation within and outside of ourselves, we risk perpetuating unequal power structures that cause harm. In our sector, settler/colonial organisations are often accused of enforcing Eurocentric worldviews on others, devaluing and delegitimising Indigenist and non-western knowledge, and taking from communities whilst providing little in return. Settler/colonial societies are implicated in the colonial project and have a role to play in dismantling it. By acknowledging this, we can try to be part of the solution.

TWO: DECOLONISATION ISN’T NEW

Decolonisation has a long history, built on decades of work led by Indigenist, decolonial and intersectional feminist scholars and practitioners. We don’t lay claim this knowledge, but rather, we learn and benefit from it every day, and are grateful for the labour and hard-won wisdom which is required to bring it into the world.

If you’re just starting on your journey to decolonise your research or social change practice, we highly recommend you read the work of leading scholars and organisations in the space, ahead of our own. Here’s a few we recommend:

- Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples by Linda Tuhiwai Smith

- Enacting Research Ethics in Partnerships with Indigenous Communities in Canada: “Do it in a Good Way” by Jessica Ball and Pauline Janyst

- Creating equitable South/North Partnerships: Nurturing the vā and voyaging the audacious ocean together by Ofa-ki-Levuka Guttenbeil-Likiliki

- Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research from AIATSIS

THREE: WE CAN’T ACHIEVE GENDER EQUALITY, OR END VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AND GIRLS, WITHOUT IT

At EQI, we’ve researched and reported on the rates and drivers of violence against women and girls (VAWG) and gender-based violence (GBV) all around the world. Although the primary underlying cause is always gender inequality, what’s less often talked about is that the rates of VAWG and GBV in communities who have or are experiencing colonisation are frighteningly, and disproportionately high.

For example, in countries which have been colonised, intimate partner violence (IPV) against women is 50 times more likely than in non-colonised countries (Mannell et al. 2021) and colonialism is one of the key drivers of gender-based violence against First Nations women in Australia (Our Watch, 2018; Alsalem, 2022). To us, it's become increasingly untenable to seek to understand or end VAWG and GBV without the lens of colonisation and decolonisation.

FOUR: IT REQUIRES DEEP, ONGOING, CHALLENGING WORK

Attempting to decolonise our practice has not been easy. For us, it’s required considering all of the ways in which so-called ‘Western’, European, and Eurocentric values and hierarchies are embedded in our work, and also how they intersect and overlap with other forms of oppression, including capitalism, white supremacy, and heteropatriarchy. This, unsurprisingly, is a huge process, and calls into question almost every part of our work – from what we prioritise, to how we seek funding, to the ways we work in communities, to the words we use, and how we use our data (and who it is owned by).

We also come across many barriers and challenges, internal and external, including navigating our own unconscious bias as we work with partners and communities in the pursuit of more equitable partnerships, finding adequate resourcing to do deep work with the care that is required, and negotiating our relationships with clients at the same time as sometimes attempting to advocate for and educate them on decolonial practices. We don’t get it right 100% of the time, and we often are required to compromise and put in place ‘more equitable’ and ‘more ethical’ practices, rather a perfect solution. We’re still learning, and have so much more to do, but decolonisation is a long-term process. This means we must remain committed to it, even if it makes us uncomfortable.

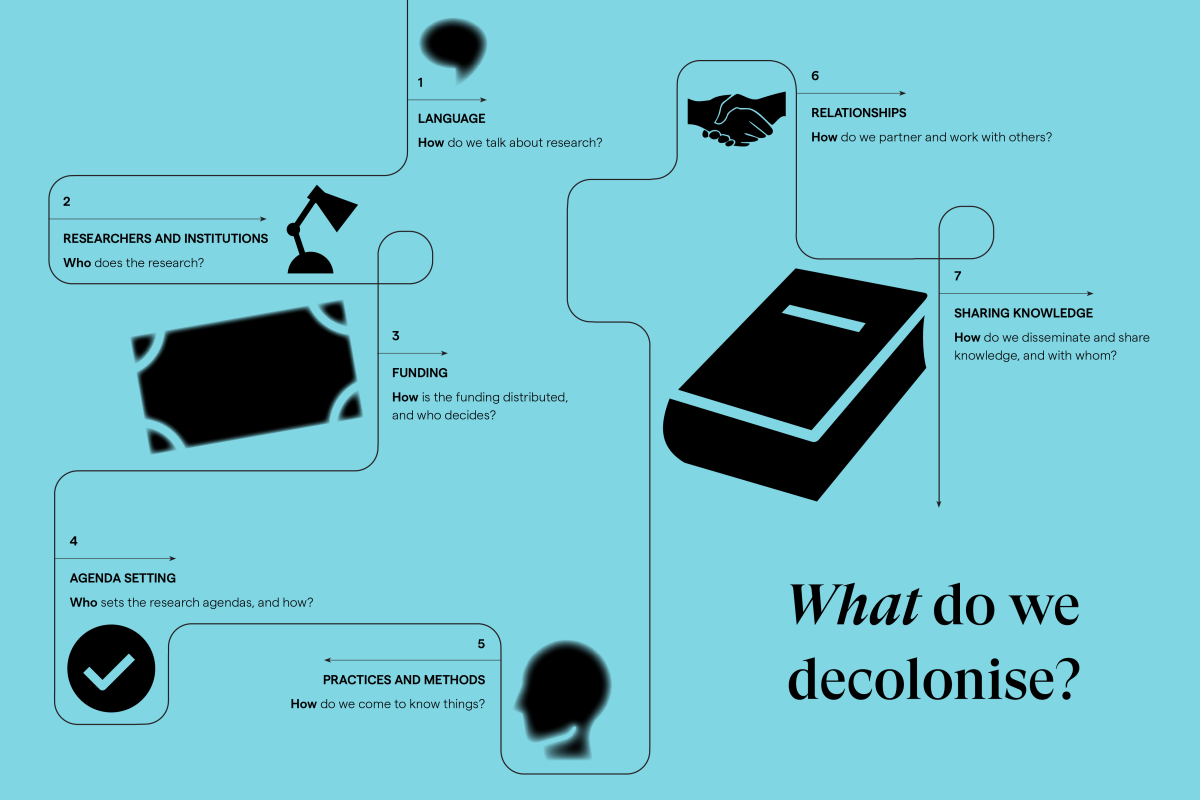

SEVEN PRINCIPLES OF DECOLONIAL RESEARCH PRACTICE

Throughout this process, we’re finding that no single component of knowledge production and research needs decolonising. All its parts deserve scrutiny. Here’s some principles which we use in decolonising our own research practice, which we hope will be helpful for you:

-

Learn, reflect and be reflexive. Acknowledge how your own beliefs, attitudes, identities and life experiences shape how you work, based on an interrogation of your own bias, world view and positionality within intersecting systems of oppression.

-

Flatten hierarchies and develop equitable partnerships. Colonialism is grounded in inequity and hierarchy. Wherever possible, work in non- (or at least less-) hierarchical ways and engage in fair and meaningful partnerships within your own sphere of influence.

-

Centre Indigenous and local knowledge lived experience and contributions. Most researchers of coloniser/settler backgrounds have had their perspectives shaped by colonial ideologies. As a result, Indigenous and ‘non-Western’ ways of knowing have been viewed as ‘unscientific’ and, therefore, ‘less than’ (Smith 2012). Therefore, to restore equity and justice to research, aim to centre non-Western frames of knowledge at the forefront of your practice.

-

Practice reciprocity and be of benefit to communities. Recognise that research must also never be driven by the sole intentions of the researcher (and/or funders, governments or other stakeholders who hold relative power) but be relevant and beneficial to the wishes of communities with which the research is conducted. True reciprocity isn’t transactional and is often ongoing.

-

Conduct ethical and safe research. Use an ethical and culturally safe protocol. This is vital for decolonising research and should adhere to the principle of ‘do no harm’ and to the highest research ethics standards.

-

Be transformative. Ensure that the research process itself – rather than just the recommendations which emerge - works to transform unequal power structures, including harmful and rigid gender norms, and gendered, colonial structures and other systems of oppression.

-

Ensure accessibility. Research findings cannot meaningfully inform policy and programming if it is only accessible to a select few. Work to ensure the ways in which knowledge and research are created and shared are accessible to a wide variety of people, including affected communities, so they can use it meaningfully.

Shifting the power imbalances in knowledge production and research is everyone’s job. Ending VAWG is impossible without it. And ethical, feminist, and decolonial research practices should become the norm.

We look forward to keeping you updated as we continue this journey of decolonising our practice. If you have any experience in these areas and have some lessons to share, get in touch with us! We would love to hear from you.

You can also download our full paper below, and we’ll be hosting a webinar on 17th March 2023. Find out more information, and register to attend, here.

Get in touch: communications@equalityinstitute.org

References

Alsalem, R. (2022) Violence Against Indigenous Women and Girls: Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences. Human Rights Council, Fiftieth Session. Geneva.

Mannell, J., et. al. (2021). Decolonising violence against women research: a study design for co-developing violence prevention interventions with communities in low and middle income countries (LMICs). BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1147.

Our Watch. (2018). Changing the picture: A national resource to support the prevention of violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children. Retrieved from: ourwatch.org.au/resource/changing-the-picture

Positionality statement (in brief)

This post was written on behalf of The Equality Institute (EQI), an organisation is led from, and largely based in, a colonial/settler context (Naarm/Melbourne, Australia on unceded Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Country, though we have also have staff based in Timor-Leste and Central Australia).

It was written by Katherine Lim (she/her), an Asian-Australian communications and social change professional. Having grown up and lived on Gadigal/Dharawal land (Sydney) and Naarm (Melbourne), and been educated within a Western system, she has often benefitted from the colonialist dispossession of First Nations peoples, whilst also experiencing impacts of racism and the intergenerational trauma of colonisation. This informs her writing, work, and commitment to decolonisation.

The above content is based on the paper ‘Confronting Uncomfortable Truths: Learning lessons for decolonising The Equality Institute’s research and knowledge practices’, prepared for EQI by Sarah Homan (she/her) with input from Loksee Leung and members of EQI’s research team. A full positionality statement for this piece of work is contained within the report.